Wage and Hour Lawsuits in California

California case illustrates how a $237,753 wage claim creates exposure to a $9,472,867 loss in court

There is a wry expression circulating within the employment law defense bar these days: "It is per se unlawful to be an employer in California." This statement derives from California labor laws that are impossible to follow to the letter; strict enforcement policies that allow no leeway for practical considerations; and extreme penalties that turn modest claims into multi-million-dollar affairs. A recent Los Angeles filing against Manpower and its client Honeywell is illustrative.

The case is a proposed class action styled Charles Keopimpha v. Manpower US Inc, ManpowerGroup US Inc. and Honeywell International, Inc., and it helps explain why job creators (a/k/a "employers") are fleeing California. According to the court filings, the Plaintiff is one of approximately 210 employees placed by Manpower at Honeywell facilities in California. The average hourly rate for the employees during the class period was $22.35.

The case is a typical example of a California "nickel and dime" wage lawsuit, asserting various small increments of allegedly unpaid work revolving around meal and rest breaks. No other states impose liability for such small technical violations in the way California does. Under federal law governed by the Fair Labor Standards Act, employers have a modest amount of leeway when it comes to tiny increments of time that would be administratively difficult to capture. This is known as the de minimus doctrine, which derives from the maxim "de minimis non curat lex," meaning “[t]he law does not concern itself with trifles.” Except in California, it's all about the trifles, and the nickels and dimes can add up to millions of dollars in penalties that far exceed any actual shortfall in employee compensation. This is thanks in part to a 2018 California Supreme Court case, Troester v. Starbucks Corp. There the Court rejected the use of the de minimus doctrine in the state, even though the California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement had for decades followed the federal rule and even issued opinion letters adopting the doctrine.

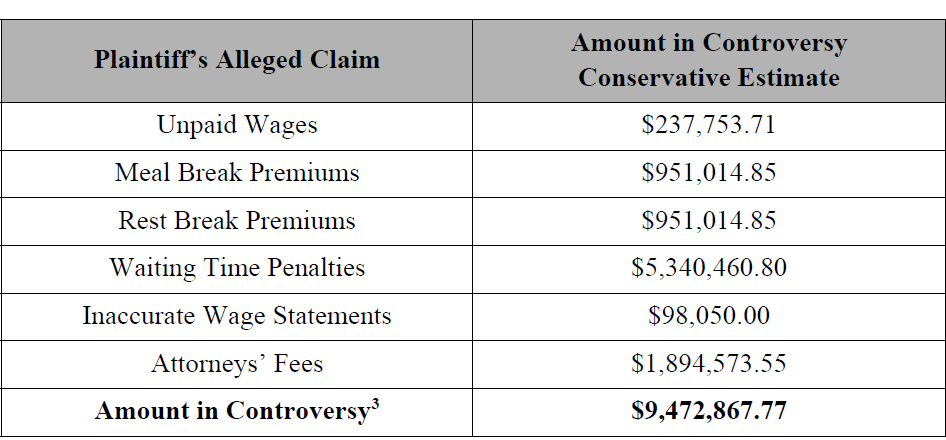

In California, close-but-not-perfect compliance results in massive exposure to a laundry list of added-on penalties. The underlying claim is just the start. To see what I'm talking about, here is Manpower's estimate of its potential exposure in the Keopimpha case, which it was required to provide for jurisdictional purposes in order to move the case from state to federal court:

As you can see, the potential recovery for unpaid wages for the entire class is $237,753. Yet the largest element of exposure, by far, is something called "waiting time penalties." These are automatic in California any time a paycheck is wrong. Similarly, the "meal and rest break premiums" are actually penalties potentially owed for the relatively modest wage exposure. Finally, the attorney's fee estimate is based on 25% of the total exposure, not the$237,000 in actual damages. Using these numbers, a wage/hour mistake in California can subject the employer to liability that is 40 times the actual amount of the mistake. No wonder businesses are fleeing the Golden State, and will no doubt continue to do so.

Nothing in this story suggests that Manpower and Honeywell have any actual liability in the case. Anybody can be sued, especially in California. The point is to illustrate the exposure that California employers face each and every day they continue to do business there.

Finally, some might suggest that the problem is the lawyers who bring these lawsuits. While everyone is free to dislike lawyers (except your own, of course), please understand that the lawyers bringing these suits are doing exactly what the California Legislature, Governor and Supreme Court want them to do. In fact, the legislature has even passed a law that deputizes every worker in the state to enforce its labor laws. It's called the Private Attorney General Act (PAGA). It allows workers to bring labor violation claims on behalf of the state against an employer or former employer. The workers act as a “private attorneys general” and can pursue civil penalties as if they were a state agency. The recovery is shared between the claimant and the state, and of course the lawyers get paid for their representation in PAGA claims.

Member discussion